On November 23, 2011 the British music manager and record producer Peter Jenner gave a talk on the digital revolution in the music industry and the need for an International Music Registry (IMR) at the Institute of Culture Management and Culture Studies (IKM) of the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna. Peter Jenner has managed Pink Floyd, T?Rex, Ian Dury, Roy Harper, The Clash, The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy, Robyn Hitchcock, Baaba Maal and Eddi Reader (Fairground Attraction), Billy Bragg and others. He works at Sincere Management and was the Secretary General of the International Music Managers? Forum, a director of the UK Music Managers? Forum and is involved on the advisory board of the Featured Artists Coalition. Currently he is a consultant for the World Intellectual Property Rights Organization (WIPO) to help in the development of? an International Music Registry. More on this project and the rationale behind it can be read in the following abridged version of Peter Jenner?s talk, which was not only authorised but also edited by himself.

In the first part of his speech Peter Jenner highlighted the completely new rules of the digital age and what do they mean for the music industry and the copyright system.

?In the mid-90s the whole digital thing started. People started to talk about digital music. It became clear to me it was a new business. There was a potential for the artists to get paid in very different way and to get a very much better deal. Or putting it another way: It was new industry in a sense that public performance leads to a different allocation of revenue from the allocation from making a recording and selling of records. It seems to me that the digital world might also reflect this. I thought that the digital world was more like radio than it was like record sales.?

However, his expectations were destroyed by the record companies which went on selling digital music like physical products.

?It was the traditional way where the record companies chopped up the money. It seemed to me an extraordinary situation. They were maintaining the same gross revenue, but getting rid off an awful amount of obligations. They didn?t have to make the records, they didn?t have to store them and they didn?t have to distribute them. They just got a file and they gave it to someone and someone gave them the money. It made their life potentially much easier.?

However, the digital world, especially with entertainment products such as music, work differently. And traditional copyright does not fit well within the new world.

?Copyright did not come down from the mountain as the eleventh item on the tablet. Intellectual property is an incredible conceit, since society and business find it very useful in some ways. It is a way for people to get paid for theirs and others creations. Intellectual property is not something like a chair. If I?m sitting on that chair you can?t sit on that chair. And if these chairs are taken away and sold, we have to buy some more chairs. They are unique, physical objects. And in some sense that?s what the traditional record business was. If I had the record, you didn?t have the record. If a shop had five records and sold them, it didn?t have them anymore. In the digital world that?s not the case. If I have a file and copy it and send it to all of you, I?ve still got mine. If you send the file to another twenty people, we have 400 files flying around.?

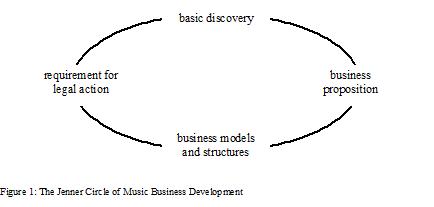

In order to understand the rationale behind the emergence of copyright, Peter Jenner introduced a circular model of technological progress, new business models and new requirements for a legal framework ? let?s call it the ?Jenner Circle of Music Business Development?.

?It is a kind of circle. It starts with a basic discovery like recording sound waves and reproducing them. The basic discovery leads to a business proposition. You can make record players, you can make records. That leads to business models and structures. And these business models and structures lead to requirement for legal action. Edison got it together. He made record players and there was a need to make records. You can?t sell the records players without having records. This leads to your business model to get a maximum of distribution of these records in order to sell more record players and so on. You don?t want to have the situation where anyone can take anyone?s record to copy it. Thus, the whole business around this basic discovery leads at the end to legal structures.?

The legal structure should protect the investments in the infrastructure, which enables the manufacturing and distribution of records. And the key factor of the record industry was to control every aspect of copying.

?And to control this industrial structure you can count. You could count and order what was going on. You could count how many labels were printed. You could count how many sleeves were made. You could control what was sold and what was being manufactured. And furthermore there was a finite number of plants. It was an industrial structure.?

?In this system [the old one] there was a revenue structure. I can make a recording as a unique product. I can control that product substantially. And can make money from that product. And consequently there is a market for that product. So it became sensible to invest in those products. And if you did it right you made a lot of money, because there is the marginal cost factor. The manufacturing cost of a physical product goes down the more you make. And since you?ve been given the monopoly right to exploit that recording and to encourage creativity and investment the profitability increases as the marginal cost of production declines. If you do that in whole global market it becomes incredible profitably. That?s why we have four ? oops three major labels left.?

?The basic thing is mass production. You can predict that there is a strong possibility that money can made from a particular recording. It?s like horse races. You put in the producer who is the trainer. You have the jockey who?s the engineer. You have the artist who is the horse. The record companies were the owners of the horses. And the music industry was all about betting on the horses. You could put all the pieces together the rider, the trainer, the pedigree, the form etc to decide whether you want to invest in that horse in that race. That sort of investment in the traditional music business would not only go into the band, the song and the producer and engineer, but also into marketing and promotion but also into tour support and so on.?

However, with the digitalisation of the whole music business, the traditional control system did not work anymore.

?When digital comes in, these things start falling apart. Digital does not work with traditional copyright systems. You can?t control it. And that was always the problem. The record companies were built on control and mass production and sales of artifacts. Suddenly, with digitisation, we are in a situation where anybody can manufacture and distribute music.?

?When Napster happened to explode they [music industry representatives] asked: ?What we are going to do now? All the people are getting their music for free. That?s not a good idea at all. So what can we do? We can try to suppress it. We can take it to court. We can close things down. We make this illegal.? They invested very heavily in DRM. They persuaded themselves they could follow these files around and every time they were used a small amount of money would come magically to the companies. And then everything would be fantastic. But of course it did not work out that way because the public hates DRM as it stops them doing things they want to do in the digital domain. The record companies wanted the public to pay far more than the file in essence was worth. When you, as a member of the public with a broadband connection and a computer, are the manufacturer and distributer why shall we pay you the same amout of money for a file as for a physical product? So it was a complete disconnect between the music industry and the public.?

?The answer was then, what we have to do is to license all this. If we can?t control it, we got to license these services. All the services like iTunes, Rhapsody, amazon.com have to be licensened. Now the problem with licensing is that we do not really know where to go for the licenses. And it is very expensive. So what was happening was that the pirated services got going because they knew that did not have to bother with licenses. So the pirates like Napster, The Pirate Bay and the rest of them had more content then the legal services. Because to get the licenses for all these records was unbelievebly complicated.?

Apart from licensing there is the problem of unbundling of content, which lower the revenues and profit margins.

?We used to sell people albums for 10 dollars or more. And so we are chopping up 10 dollars into sections. If you want to listen to the song you have heard in the radio, you have to buy the album. We have gone from a 10 dollar item to 50 cent item.?

The digitalisation changed the whole game in the music industry ? the production, dissemination, perception and usage of music.

?What we are selling in the digital world is services. As a consumer you can access all the music somewhere, somehow in the world for nothing. You just need time. But there is a continuum between the people who are cash rich and time poor, and people who are time rich and cash poor. How should we deal with people who are drowning in content? In a record store you have a finite amount of choice. Now that you have an infinte amount of choice, the next problem is choice, and the problems of choice. There are various ways of remembering music, and the services that help you find what you are looking for are the sort of service which becomes interesting in the digital economy.?

?Then we can also start thinking about the function of the recording. The recording used to be something you could only do by going to a very expensive studio, which was very capital intensive. Now you are talking about a different situation where all becomes much cheaper.?

?Then we can also start thinking about the function of the recording. The recording used to be something you could only do by going to a very expensive studio, which was very capital intensive. Now you are talking about a different situation where all becomes much cheaper.?

In the earlies times the record company made a record and promoted it. ?Now we should think about continuums. One is not making THE record but one is making a series of recordings. The fans might want the original demo or they might want the first band rehearsal. They might want the first recording of it with the backing track, which was finally used. They might want to hear it with the early vocals and so on.?

?So it is a question of finding services which answer to the public?s new demands from services which the new technology enables. Above all we can suggest that the prime need is for access. Consequently anyone providing a service needs to have access to all the music. And if you want to have access to all the music you need to able to license it or to pay for it. My position is that I cannot see how we can escape from some sort of ?blanket license? approach. Because finding the people who own the recordings is very, very difficult. And that is the problem. More difficult still is finding the publishers and the other rights holders in the underlying works.?

This leads to the second part of the talk, in which Peter Jenner highlights the rationale for an International Music Registry.

?A friend of mine, Jim Griffin, tried to license publishing for a service called Choruss which he tried to put together with Warner Bros. He went to the American Music Publishers? Association, he went to Harry Fox, who was like the American collection agency for the publishers of the mechanical works. And they could only give him the names of 40 percent of the publishers of the published works. And they would not guarantee that the information was correct. And a similar situation occurs in Europe. We don?t know who owns what and where. And consequently to ask people to license material, when you don?t know who owns it, is asking the impossible. So the EU said: ?Ok, let?s try to make this simpler.? So a couple of major publishers and some of the collection societies responded to this, because they realized that they will get even more trouble. And so they decided to put together a Global Repertoire Database.?

?We thought this was not enough as it only really addressed the issues of music publishing rights within the EU and so we started thinking about an IMR ? an International Music Registry ? and thus WIPO (the World Intellectual Property Rights Organisation) comes in. Along with some other colleagues, we came to the conclusion what was needed was to make a real effort to start getting together a really global International Registry of registries of Music. But the idea is to take all the registries that currently exist or are planned and try to get them to talk to each other. That?s the long-term aim. In the short term it could be rather more restricted. We get some of the registries to talk to each other.?

?We have got to make it faster, simpler and easier for people to pay and for the money to be allocated. We are talking about tiny sums of money. You can?t take a penny or a cent and chop it up in 15 directions and send it to 15 different people. In this context it is madness to spend a pound to distribute a penny. So we have to think about what is a sensible way of enabling the technology to do what it can do. Enable the people who have the ideas how they want to present and curate and to filter music to the people who want to listen to that music. And we also need to find a way that generates enough money to enable enough fresh music to be created, because as a society we thrive on new music and other creative work.?

?So I hope we will have a mixture of blanket licenses and services whereby the end-user can order music, and that leads a couple of cents coming back to the creators and their investors. On top of that I would like to see special value added services, which cooperate directly with the artists or groups of artists or labels. There will be, I hope, a whole series of different sorts of business models and a whole series of different sorts of people distributing music. There will be a plethora of different types of services, which would come and go. And in 20 years time you will sit there and say: ?It?s very different ? isn?t it? Can you remember when Peter was talking about what would happen in the future? None of it happened like that. That Jenner gave us a load of old tosh.?

Anyway, thank you very much.?

Advertisement

Like this:

Be the first to like this post.

posterior michelle obama adam lambert arrested shroud of turin barkley beltran space ball

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.